Story Background

“The Variable Man” is a novella by Philip K. Dick, first published in Space Science Fiction in July 1953. Pages numbers come from Paycheck and Other Classic Stories by Philip K. Dick (New York: Citadel Press), pp. 163–219.

Plot Summary

Chapter One: Terra Security Commissioner Reinhart discusses planning for the war with Centarus with Kaplan. While the war is not yet being fought, it is being incessantly planned for. As new weapon systems are developed, their impact on the future conflict is placed in computer systems. The outcome is a calculation of the odds of victory for Terra. No weapons are made, only planned. When the odds are enough in Terra’s favor war will commence with the object of ending the Centauran blockage of Terran expansion into the galaxy. Over time the computed odds are slowly moving in Terra’s favor, giving confidence to the war planners of victory. Reinhart contacts Peter Sherikov, the head of Military Designs. Sherikov is Polish and described as heavily individualist, leading Reinhart not to fully trust him or fully believe in his commitment to the war effort. Sherikov is working on a project called Icarus. The Icarus is a ship that was originally designed for faster than light travel. However, when it re-enters normal space-time the result is a massive explosion. Sherikov’s plan is to redesign Icarus into a weapon that will reenter space in the Centauran sun, destroying their civilization in one blow. The result of this new weapon is the first calculation that Terra will with the war, at 7-6 odds. Reinhart begins to move the entire planet to war production. Kaplan sends a report to Reinhart mentioning that the use of a research time bubble carried someone from the past into the present. Almost immediately the computer calculations begin to vary dramtically, sometime predicting a victory for Terra and others times for Centaurus. Kaplan realizes that this is caused by the “variable man” from the past, which the machines could not deal with.

Chapter Two: Thomas Cole from Nebraska is in Central Park and realizes that he has been carried far from his home. He is confident that he will find work because he is a skilled artisan and jack of all trades, capable of taking on a variety of odd jobs.

Reinhart arrives in New York with E. Fredman from the Histo-research office. They are looking for the man from the past. Cole is driving his horse-drawn cart around and he slowly beings to realize how strange the town he has found himself in is. The homes in the city look strangely modelled. The woman walk around topless. When he asks about work, he is directed to a government office that he never heard of before. The people he meets are amazed to see Cole’s horses, which have long been extinct on Terra. Cole escapes a encounter with the director of the Federal Stockpile Conservation, escaping into the nearby towns, and soon learns that it is 2128.

Cole’s escape is reported to Reinhart, who is worried that until the “variable man” is accounted for, the war plans cannot go forward with confidence. He later learns that Cole was spotted on the highway with a horse-drawn cart and was bombed by airships.

Cole, who survived the bombing run but lost his cart, horses and tools, is taken in by some children. This scene is important. Cole learns that work is called “therapy” and that no one repair broken things anymore. Cole may be unable to find work because the culture prefers to throw away broken technologies. Yet, the children is amazed when Cole easily repairs a box-shaped vidsender. One of the children, runs to tell his father, Richard Elliot.

Chapter Three: Richard Elliot reports the repair of the vidsender to the authorities and it finds its way into the hands of Reinhart who realizes that the repair confirms that Cole has not been killed. The repair job was queer, involving a lot of improvisation and transformation of the wiring system, but it worked nonetheless. Even more striking, Cole has improved the toy vidsender so it worked as well as the industrial ones used in the military to move items up to eight light-years. Reinhart begins to understand why Cole’s presence is so disruptive. Not only does he introduce uncanny skills to the world, he comes from a world with a very different Weltanschauung. Meanwhile the odds are still is disarray. Not only the war effort, Reinhart worried, but the entire social structure cannot handle the “variable man.” Sherikov wants to study the phenomenon more, but Reinhart insists that Cole must die to rebalance the situation.

Sherikov intercepts and kidnaps Cole bringing him to a laboratory under the Ural Mountains. Sherikov explains that Cole is necessary for Terra because he brings in the possibility of creativity in a world dominated by machines. Not only can Cole’s presence help transform that ethic, victory in the war is essential for human progress because Proxima Centaurus—a decrepit and declining empire—has limited Terra’s ability to expand. Sherikov charges Cole with getting Icarus to work by fixing the broken control turret. In exchange for this labor, Sherikov promises to return Cole to his time.

Chapter Four: Both Terra and Centaurus are busy preparing for war. Reinhart deduces that Sherikov has secured Cole. He visits Sherikov’s lab in order to place him under arrest. A battle breaks out between Sherikov and his defensive forces and Reinhart’s security forces. Reinhart proves triumphant is reaches Icarus but Cole is no longer there. Cole attempts to escape but after he leaves the Sherikov’s lab, one of Reinhart’s men orders a phosphorus bomb dropped on Cole’s position. Cole’s body is eventually found. He is alive but heavily injured with phosphorus burns. With Icarus complete and Cole out of the picture, the war beings. Soon after the orders are sent to the military, the new computation show odds of 100-1 against Terra. After a short and brutal war, which involved the apparently failed deployment of Icarus, the war ends with Terra defeated.

In the final analysis, it is revealed that Cole fixed Icarcus so that the faster-than-light device would not explode when reentering space-time. Icarcus, therefore, entered Proxima Centaurus but did not explode. While this led to defeat in war, it also made conflict with Centaurus avoidable. In the future, other Icarus ships could simply evade the blockade, leaving that old empire to decline and Terra to enjoy a renaissance of exploration. In the final scene, Sherikov and Cole work on a device that will democratize Terra, creating a direct democracy by allowing each citizen to vote on issues instead of waiting for the bureaucracy and the ruling council to decide. Authoritarian figures like Reinhart would be less likely to emerge in such a system. Cole agrees to help Sherikov finalize the device.

Analysis

“The Variable Man” is the longest work Dick published during his prolific first two years. It may be the longest science fiction piece he wrote before his novels. He was working on some mainstream novels at the same time. It is as thematically complex as many of his novels, but the core theme is one the relationship between humans and technology. Humanity has made everything, including the decision to make war, into a mechanical calculation. Any human autonomy is lost. “The machines only do figuring for us in a few minutes that eventually we could do for our own selves. They’re our servants, tools. Not some sort of gods in a temple which we go and pray to. Not oracles who can see into the future for us. They don’t see into the future. They only make statistical predications—not prophecies.” (195) This statement by Sherikov summarizes the nuance in Dick’s technophobia. Technology, when suppressing human agency, is a dangerous force. When used as a tool, it can be liberating. In this way Dick had much in common with the twentieth-century anarchist interpretation of technology.

The hero of “The Variable Man” is a jack-of-all-trades, the only person in early 22nd century Terra who could apply the flexibility necessary to rework technologies and solve technical problems. That is something that is mostly lacking. People can design weapons or consumer goods based on plans, but no more than that. Deviating from the plan or finding creative alternatives is beyond the capacity of the masses of technocrats. Cole, who came from the early twentieth century, was from a period when people had a more healthy relationship with technology. “Before the wars began. That was a unique period. There was a certain vitality, a certain ability. It was a period incredible growth and discovery. Edison. Pasteur. Burbank. The Wright brothers. Inventions and machines. People had an uncanny ability with machines. A kind of intuition about machines—which we don’t have.” (186)

Another consequence is the loss of individuality. Sherikov and Cole are kindred spirits because they both believe in the importance of the individual over the institution. People no longer have jobs or employment, but attend “therapy.” This is one of the most interesting euphemisms for labor I have ever seen in science fiction, but also one of the most difficult to interpret. Apparently work is seen as an essential part of a well-balanced and regulated life (like a machine?). Cole is seen as odd because he seeks out work to make a living.

Yet another consequence of human dependence on machines was the replacement of democratic institutions with an authoritarian technocracy. The odious nature of this system is reflected in the character of Reinhart (who as far as I could notice was not given a first name). Unlike the very American “Thomas Cole,” Reinhart reminds us of the Old World values and institutions. Reinhart is brilliant (he quickly sizes up Cole and the danger he poses), hierarchical, intolerant of dissent or a breakdown in order, and violent. Cole, on the other hand, embraces the values of cooperative, self-sacrifice and autonomy, the very values that a well-functioning democracy depend on. He is the Dick’s vision of a yeoman farmer for the industrial age.

Related to the question of stagnation is Dick’s believe in the importance of creativity, exploration, and cultural rebirth to the survival of civilization. Proxima Centaurus is an old empire long past its prime and no longer capable of expanding even though it can still defeat the comparably upstart humans. Terra is at risk of the same fate for two reasons: the reliance on machines and the end of the frontier. The individualist Sherikov realizes the necessity of expansion for cultural revival. “Terra is hemmed in on all sides by the ancient Centauran Empire. It’s been out there for centuries, thousands of years. No one knows how long. It’s old—crumbling and rotting. Corrupt and venal. But it hold most of the galaxy around us, and we can’t break out of the Sol system. [. . .] We must win the war against Cantaurus. We’ve waited and worked for a long time for this, the moment we can break out and get room among the stars for ourselves.” (195) The necessity of a frontier informs much of Dick’s early works, including the novel The World Jones Made.

In “The Variable Man,” Dick critiques the culture of waste that he saw building around him in early 1950s America. Thomas Cole looks back to a time even before Dick’s, when jack-of-all-trades skilled workers had control over the technologies in use. By the early 22nd century this autonomy of humanity over the machine had ended. He shows that it was not only a question of autonomy, but also one of waste and kippilization (to predict the term’s application in a later novel). We see that the entire Terra war effort is based on a principle of almost instant planned obsolescence. Weapon systems are not even build. They are only planned and tested. Immediately planning for the next generation begins. This is not terribly far what takes place in The Zap Gun. Dick seems to be making a point about the essential value of production for use sake. The entire state structure is devoted to production for potential use only. The result of this is a great waste of human effort, going nowhere.

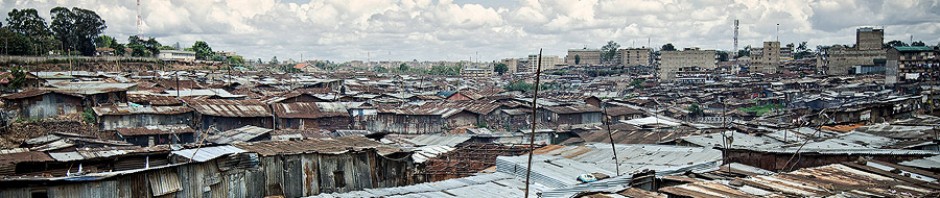

I do not know what this has to do with the story, but it seems to be an illustration from the original publication.

Resources

Wikipedia entry for “The Variable Man”

Murray Bookchin’s argument for human-scaled technology.

Short introduction to Arnold Toynbee’s theory of history, which looks at the role of decadence in imperial decline.

*Note: Dick was certainly familiar with Toynbee as he is mentioned in Time Out of Joint.

Audiobook version of “The Variable Man”

Pingback: Waterspider | Philip K. Dick Review

Pingback: Philip K. Dick’s Philosophy of History: Part One | Philip K. Dick Review

Obviously within his fictional reality,Dick thought that only individual craftsmens could bring salvation to a society dominated by technocracy.The comment I made on your essay of the same short story,pertains to your analysis here.

This was one of the best of his early short pieces,and probably one of the best short stories of his career.It is written from an historical perspective,with no real hint of his interest in metaphysical themes,but it does contain spirituality I think,that is the core of the weirdness associated with such happenings.It doesn’t seem to have been written in a rush,and is almost like the first draft of a novel.I think it’s much better than “Solar Lottery”,and would have been a very fine one.